Your Kidney Stone

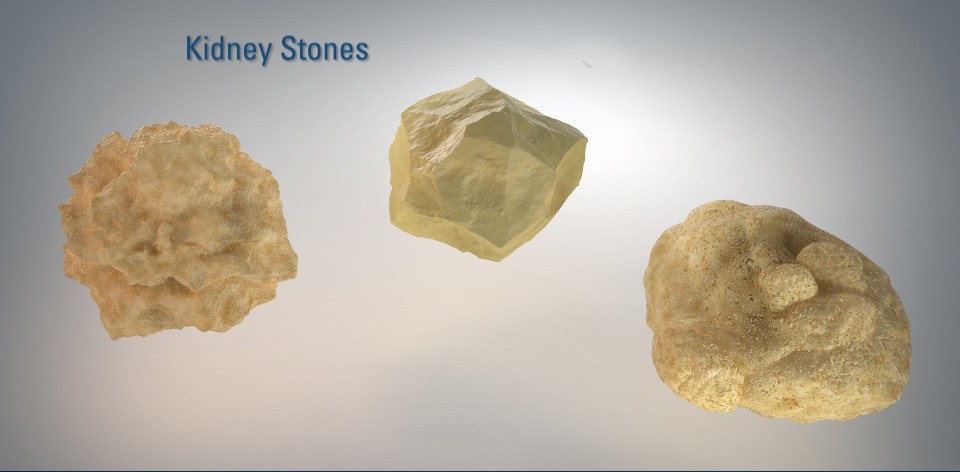

A close look at your kidney stone

Formation

It all starts with waste products that the kidney filters into the urine. Usually these substances pass harmlessly out of the body. In some cases, though, if these substances become too concentrated in the urine, they may form a solid mass of crystals that can increase in size.

Most people produce enough liquid in urine to pass the crystals and other stone-forming chemicals – calcium, oxalate, urate, cystine, xanthine and phosphate – out of the body. But when these substances become too highly concentrated in your urine, a kidney stone can form.

Common Types

Calcium stones – The most common type of kidney stone forms in two primary ways: calcium combining with oxalate in your urine (calcium oxalate) or a high amount of calcium plus increased pH levels in your urine (calcium phosphate).

Uric acid stones – If you eat a high-protein diet, are obese, or suffer from gout, you may have an increased level of uric acid in your urine. If uric acid becomes too concentrated, which may occur when the urine pH becomes abnormally low, or if uric acid combines with calcium, it can form a stone.

Struvite stones – If your kidney or urinary tract becomes infected, you may develop struvite stones, which can grow rapidly and become very large in size. Left untreated, they can cause chronic infection and seriously damage your kidney.

Cystine stones – These rarer stones are due to a genetic disorder that causes the amino acid cystine to leak into urine from your kidneys, forming crystals that may accumulate into stones.

Location

The location of your stone is critical. After a stone forms, it may stay in your kidney or travel down your urinary tract. Often, small stones will pass through the body without causing much pain. However, larger stones can get stuck somewhere along the path – your kidney, urinary tract, bladder, or ureter – blocking the flow of urine and triggering severe pain.

Your doctor may use different terms – like nephrolithiasis (kidney), urolithiasis (bladder or urinary tract), or ureterolithiasis (ureter) – to describe your stone location before determining which treatment is best for you.